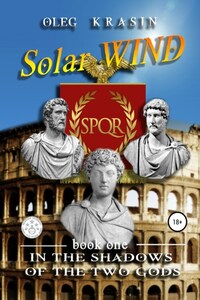

Solar Wind. Book one

He grew up during the time of two emperors who were people, and then became Gods. He taught rhetoric and philosophy, not martial art. He was preparing to rule Rome in civilian life, but he had to fight.

MARCUS AURELIUS ANTONINUS

The emperor-philosopher, for a moment, thanks to him, the world was governed by the best and greatest man of his age.

| Жанры: | Биографии и мемуары, Историческая литература |

| Цикл: | Не является частью цикла |

| Год публикации: | 2022 |

Читать онлайн Solar Wind. Book one

Книга заблокирована.

Вам будет интересно